Betty Kershner, PhD. is a Registered Psychologist specializing in both adults and children, from infancy onward, and recently moved her office to West Toronto. She has worked with and consulted in a wide range of settings and is familiar with many types of concerns and solutions. She is able to offer assessments and treatment. Please Contact her here.

Writing nearly 100 years ago in Mourning and Melancholia, around 1915 – 1917, Freud was developing his ideas about narcissism. He was able to push his thinking further by exploring the difference between normal mourning and pathological melancholia. Freud’s thinking on this topic contributed to his formulation of super ego and the sense of guilt, as well as narcissism.

Freud described mourning as a reaction to the loss of a loved one, or the loss of an abstraction which has become symbolic of love, such as an ideal, one’s country, one’s way of life or intended way of life

He described mourning as a reaction to the loss of a loved one, or the loss of an abstraction which has become symbolic of love, such as an ideal, one’s country, one’s way of life or intended way of life: one’s city and family wiped out by the Atomic bomb – one’s intended future life with a partner, running away from family, community and from familiar routines, gone. A strong negative reaction to such events is understandable and expectable.

Even while mourning may involve ways of thinking, feeling and being that are intensely painful and different from normal life, we do not, at least not until DSM-5, regard that as an illness. We expect the sufferer to get better with time and mourning to diminish.

With normal mourning, there often is loss of interest in the outside world if it does not involve the loved one, and loss of capacity to love a new object. When normal mourning is completed, the ego is free again and can invest in new love.

For some people, the same events, the same kind of loss, instead of mourning produce what Freud termed “melancholia”.

in melancholia … there is additionally a kind of losing of oneself as one knew and valued oneself

In melancholia, in addition to loss of the loved object or ideal and the temporary loss of the ability to love, there is additionally a kind of losing of oneself as one knew and valued oneself, involving the lowering of self-esteem, feelings of self-reproach, and expectations of punishment. It is particularly the feelings of self-denigration that distinguish between mourning and melancholia: as Freud terms it, “a disturbance of self-regard”.

In melancholia, absorption into that loss is prolonged and leaves little or no energy for other pursuits, such as new love or deep interest in others.

The experienced loss involves something more ideal and idealized than realistic, and one cannot see clearly what it is that has been lost, neither the bereft nor those around her. One knows “who” but not “what” has been lost along with the departed person. The real meaning of the loss is withdrawn from consciousness: it is unconscious.

There is a kind of melancholic inhibition and withdrawal from real, felt participation in life as Ego becomes absorbed in mourning and becomes unavailable for other interests. Grief and reaction overtakes everything and keeps the bereft from real involvement in anything else. What involvement develops can take on a kind of “pseudo”, disinterested quality. It is puzzling to others, who cannot see what is so absorbing to the sufferer.

In mourning, the world is a poorer place. With melancholia, it is the ego that is poorer: worthless, incapable of achievement, morally despicable, ugly. The melancholic loses self-regard and feels diminished, damaged. This person may vilify herself, expect to be cast out from normal society and punished, may abase herself. She may commiserate with others for being connected to her. She may invite degradation, believing it is deserved.

The ego becomes identified with the lost object

In melancholia, the work of decathecting, of disengaging from the lost love object, is blocked. The loss of love is blocked by withdrawal of that love into the ego, an identification of the self with the lost object. Libido, meaning the sexual drive and the life instinct, instead of being displaced onto someone new, some new love, becomes withdrawn from the ego. The ego becomes identified with the lost object.

The bereft attempts to loosen the fixation on the object by disparaging it, and the self.

There is a delusion of moral inferiority, that one has always been bad and morally inferior. This may be accompanied with sleeplessness and refusal to take nourishment – the life instinct may be ignored, as one withdraws from what is needed to sustain life.

It is fruitless to contradict people who are suffering so

It is fruitless to contradict people who are suffering so. They are convinced that they see the truth of the situation – and that others do not. Others can become discounted when the melancholic views them as failing to grasp basic truth. Their opinions, feelings and experiences do not really matter in this scheme, since the melancholic believes that others and not themselves are living a kind of lie. The disregard of self spills over into disregard of others.

What is this self-hate about? Where does it come from?

It is secondary to the internal, distorted work of mourning that is consuming the ego of the melancholic.

Under normal circumstances, when one feels critical about oneself, judges oneself negatively, one feels ashamed and wants to hide it from others: to hide their shame away from sight. In melancholia, the mourner lacks shame, regardless that she may say she has done wrong: she derives satisfaction in self-exposure because, at bottom, those very complaints are against someone else, not herself. She wants the complaints known but dares not voice or even think them openly.

The complaints made against the self may not seem to fit, but they do fit someone else, someone whom the melancholic loves, has loved, or believes that she should have loved.

What is key here is that the self-reproaches really are reproaches against another person, the loved one, shifted onto her own ego, with a few genuine self-reproaches scattered among them, helping to mask the truth.

The behaviour represents a constellation of revolt, as opposed to the submissiveness that would be expected if the person really were ashamed.

For loss to be felt this way, a strong fixation on the loved object must have been present on a narcissistic basis, so that when the object is lost, the regression is to narcissism. The narcissistic identification substitutes for the identification of a new object love – so the relationship need not be given up.

The mourner blames herself for the loss: feels that she has willed it. There are battling feelings of love and hate – conflict due to ambivalence. One part of the ego is set against the other. The critical agency is split off: the conscience is ill, and dissatisfied with the ego on moral grounds: a key feature. A manic quality can develop.

If the love becomes displaced in identification with the lost object, the hate comes to the forefront, turning to abuse, debasement, sadistic satisfaction from suffering, and self-torment. Sadism turned on the self is the perceived revenge on the lost object. In this way, the bereft avoids the need to express hostility to the object openly.

The bereft loses her own self-respect. Object loss has resulted in loss to her ego.

The pre-existing ego is overwhelmed and lost through the identification with the object and narcissistic regression into the object: the object becomes more powerful than the ego.

in melancholia, there is a pathological combination of mourning and narcissism

To rephrase: in melancholia, there is a pathological combination of mourning and narcissism. Melancholia involves: loss of the object, ambivalence about the object and the loss, and regression of libido into the ego – into narcissism: according to Freud, narcissism is the one determinant factor that separates melancholia from normal mourning. The relationship to the lost object was complex, was complicated by ambivalence. The ambivalence of the love relationship comes to the forefront with the loss. It hinders progress along the normal path toward resolution. The ambivalence may be repressed; it may be associated with trauma. By returning to the beginning of that love, one may be able to become conscious of it and then to work through the ambivalence and the loss.

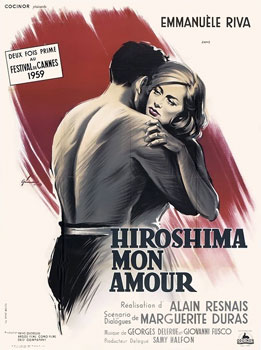

Alain Resnais, producer-director of Hiroshima Mon Amour, generally is considered a member of the French “New Wave” cinema of the late 1950’s and 60’s: a reaction against Hollywood style and commercialism. This film is from 1959.

He instead considered himself a member of the “Left Bank” group who, in addition to that Hollywood rejection, shared a commitment to modernism and an interest in left-wing politics. His anti-war sympathies underlie his work.

Prior to “Hiroshima Mon Amour”, Resnais had made “Night and Fog” in 1955, an influential documentary about Nazi concentration camps (referred to by Woody Allen in Annie Hall in his quest to educate his girlfriend, as evidence of his sensitivity and erudition). It was one of the first documentaries about the camps, but Resnais struggled with the question of how to portray something that he believed was too horrible to comprehend. He developed an indirect approach, believing it necessary to move toward his subject obliquely, circuitously, more or less illogically, in order to open the possibility of creating a visceral reaction in his audience. His documentary was more about the memory of the camps than about actual past existence, believing that a realistic style could not confront the enormity of the horror.

“Hiroshima Mon Amour” arose from a commission for Resnais to make a documentary about the atomic bomb. It became his first feature film. Resnais struggled with how to film incomprehensible suffering and concluded that one could only speak about the impossibility of speaking about it. He developed unconventional narrative techniques, focused on the theme of troubled memory and imagined past: on consciousness, memory, imagination and time.

Starring Emmanuelle Riva making her screen debut and Eiji Okada as her lover, the film was written by Marguerite Duras. Resnais often worked with writers unconnected to cinema. Born in Saigon in 1914, Duras grew up with her mother and two siblings in Indochina, in relative poverty after the early death of her father. She went to France at age 17 to study, was drawn into political science and became a communist. Duras worked for the French government office representing Indochina. During WWII, she worked for the Vichy government but was a member of the French resistance. Her husband was deported to Buchenwald, but survived.

Short but compact, the film utilizes a non-linear structure: past and present co-exist. Resnais films the memories of two strangers: the plot is simple and the emotions are complex. The journey is through their emotional terrain, their memories, and their dialogue. Their faces and bodies are the landscape. Exteriorality doesn’t matter. It is an exploration of their souls.

The baffling repetition of words and ideas, the confusion of the words, conveys a dream-like quality. We focus on the gradual, complex verbal revelations and the quiet, insistent striving for connection. There are only three scenes and only two important people in the film.

Their conversation and embrace in bed take up the first third of the film. He is an architect rebuilding Hiroshima, focused on creating the future, the new, from the ashes; it is said that many Japanese at that time did not want to face what had happened, wanted to deny it, ignore it and focus only on the future. We first see them at a hotel: “The New Hiroshima”. She is an actress in a film about peace set in the place where the war’s destruction was dramatically catastrophic: dramatic enough to bring an end to the war. What could be more anxiety-producing at that time than the Atomic Bomb and its potential to end life on the planet?

Indeed, for our film group, this time and place provides a kind of ultimate backdrop of anxiety in which to look at love.

The camera does not waver: there are no cuts from one face to the other: the filming of the actors is as close as possible such that sometimes you can’t tell what you are seeing.

When first we see them, their bodies sparkle, perhaps with sand: their surfaces have a similar appearance to the close-ups that we are shown of the earth in its oddity, after the explosion of the bomb.

The story is the short, two-day affair between the French actress and Japanese architect. It is not focused on events. There is a slow evolution of various levels. The focus is on the inner life, the words, the exchange of ideas.

Their conversation becomes tormented and agonizing, mesmerizing, dreamlike. Neither of them has a name. War is personalized and psychologized: the bond of love allows the memory of the horror to come forth.

Both of them are “happily married”. This sudden affair is an outgrowth of the heroine’s prior love and loss in WWII in Nevers with a young German soldier, for which she was ostracized by both her community and her parents. She tells him, “I met you, I remember you”.

“Just as the illusion exists in love, that you can never forget, so I was under the illusion I would never forget Hiroshima.”

Now, the exquisite happiness that she finds with her Japanese lover reminds her of that earlier love and loss. It returns to her in vivid intensity, in flashbacks that seem to occur in present time. She speaks to her Japanese lover as if he were her German, her “amour impossible”. We don’t know much about them. At first, when he tells her repeatedly that she has seen nothing, that there is nothing to see in Hiroshima – when he denies loss – she says that she knows of loss as well. She tells us, “Just as the illusion exists in love, that you can never forget, so I was under the illusion I would never forget Hiroshima.”. She tells him, “Like you, I know what it is to forget. I am endowed with memory”. He, in the meantime, denies it all. “You saw nothing”. She sees through him. She knows all too well that there is more than “nothing”: “I have struggled with all my might not to forget. Like you, I forgot. Like you, I longed for a memory beyond consolation, a memory of shadow and stone. I struggled against the horror of no longer understanding the reason to remember. Like you, I forgot.” She takes his loss as a given. Her refusal to deny or ignore the evidence of loss all around her, her simple insistence that loss and suffering exists, the unspeakable, breaches his defenses and he reveals, in response to her questioning and responding to her candor, that he lost his family.

She is accustomed to casual affairs and thinks that this will be one of them. She tells him: “I have dubious morals”, but is willing to declare that it is the morals of others about which she is dubious. “It will begin again”, she tells him, speaking of war, of destruction, suffering and loss. She does not hide her anger and dismay at the principal of inequality advanced by one people against another, one race, one class, against another. But much as she faults the others, those who bring war, she denigrates herself, looking forward to the “lies” and escapes of infidelity.

But it is not a casual affair. This one is different. Perhaps part of it is due to the setting; being in Hiroshima, the site of devastation, intense suffering and loss. And part of it is due to his loss: the commonality of suffering. They recognize that in each other. While he seeks to know more about her, to find out who she is and how she became that person; her focus is on her own experience. She uses him to allow herself to look at it afresh, using his interest, his caring as the support she did not have when the loss was fresh, to sustain her and allow her to confront it.

She was 20: he was 22 – both in the glory of their youth.

He: “I somehow understand that it was there (Nevers) that you were so young you belonged to no-one in particular.”

Here, he identifies with her, with her youth, her sense of power and possibility, her youthful narcissism. He is able to fall right into it, to identify with it and through that, with her circumstances.

“Was I dead when you were in the cellar”, he asks? He steps into the role of her dead lover. She gives him that role and he takes it up actively. He joins her in a kind of folie a deux. They share the feelings of that youthful, narcissistic time.

“You’re dead”, she tells him. She is speaking to the Japanese man, but really to her dead lover.

She equates the pain of her German dying and the pain of her suffering in the cellar. She has identified with her German. “I didn’t find the slightest difference between his dead body and my own.” Her Japanese steps into that identification. By becoming her German, he brings it back and creates the opportunity to confront, to reconfigure and resolve.

She screams, “I was so young once”. She is absorbed in the narcissistic regression, the feeling of invulnerability that was smashed when her German lover died and her intended idealized future was lost. His slaps across her face bring her out of it, and she smiles at him. He has understood what that moment was for her and that she should not stay there, in that regression to narcissism.

She dreams of Nevers at night but does not think about it during the day: it is an unconscious force for her. She describes her madness: “I was mad with hate. All I cared about was hating”. He understands and she recognizes that he understands.

As he sees her react with great sorrow to the parade of demonstrators, he thinks that he loves her: “You give me a tremendous desire to love”. He wants to rekindle that ability for himself. She is someone who can feel the loss he denies and awaken him to it. Bit by bit, he questions her.

With yearning and desire, she tells him both that he is good for her and that he destroys her. At war with herself, there is a part of herself that she wants to destroy. Then, she calmly tells him that there will be no more meetings; that he will go away: back and forth she swings, ambivalent.

He cannot think of her as a real person: it is too overwhelming. He must think of her as an abstract concept.

He becomes increasingly obsessed with her as he sees her struggle, the pull and push of her attraction to him and to her past, her absorption into it and her inability to master it. He follows her while keeping a distance, attempts to convince her to stay in Hiroshima, at least for a while. She fantasizes that he will come to her, take her in his arms and she will be lost: but he does not. Instead, he tells her, to her obvious disappointment, that in the future, he will have forgotten her but then, after other “adventures”, will remember her as emblematic of the tragedy of forgetting. He cannot think of her as a real person: it is too overwhelming. He must think of her as an abstract concept. Neither of them is yet ready or able to commit to a future, to move on away from the past.

But his continuing presence, his refusal to leave, his availability, his questions, his attunement during those moments when she is able to open, lead her to slowly expose the layers of pain that she has carried for 14 years. Flashbacks reveal her past. His twitching hand in his sleep leads her to relive the twitching hand of her German as he lay dying.

She is telling her story for the first time. She has not told her husband, not told anyone before him. This break-through into her deep pain, her new-found ability to confront it, gives him hope for his own possibilities. Painful and repulsive as it is – madness – it is something that both of them know is needed for healing.

She tells him, “It’s horrible. I remember you less and less clearly”. She does and does not want to forget: “I tremble at forgetting such love”.

She begins to move on and out, changing pronouns from: “I begin to forget you”, to “I was to leave with him”. She is beginning, tentatively, to move out from that symbiotic identification and merger, forward to the Japanese as a man in his own right, someone outside of the old traumatic identification: toward a new object of new love.

But first she must do the work of working through her mourning, which has only now become available to her. Her encounter in and with Hiroshima has broken her out: she will be able to move forward.

Such naked intimacy filmed so unconventionally, de-glamorizing and almost depersonalizing for the sake of telling the story that is still happening in her mind in endless repetition, opens the trauma to us, shows us the enormity and how it overwhelms rationality.

The film was considered a plea for peace and for abolition of atomic warfare. Also, it is about the cruelty inherent in personal growth, in having to shed your past, your bonds with the dead – the pain of loving and losing and the greater pain of having to let go of the pain we sometimes wish to hold onto.

The last bar that we see them at is “Casablanca”, named on its marquee outside the door. The boy does not get the girl. The girl leaves on a plane without him. There are no Hollywood happy endings here, but there is recognition and confrontation, support, growth and an acceptance of love and loss in a time of anxiety.

Betty Kershner, PhD. is a Registered Psychologist specializing in both adults and children, from infancy onward, and recently moved her office to West Toronto. She has worked with and consulted in a wide range of settings and is familiar with many types of concerns and solutions. She is able to offer assessments and treatment. Please Contact her here.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.